Echoes from the past: Dr. Sanderson’s inspiring family tree

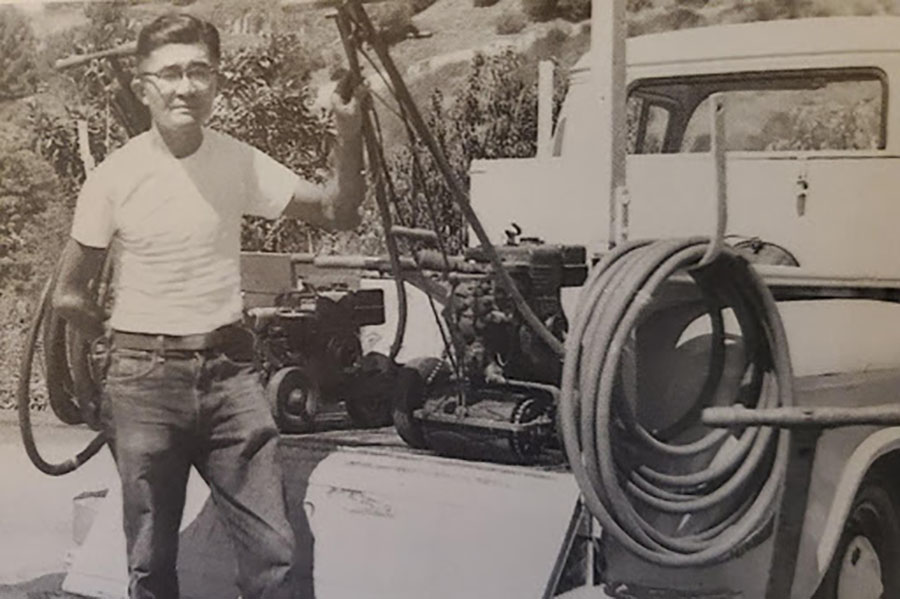

Dr. Robert Sanderson’s grandfather, Toshio Yamagata, stands beside his gardening truck in Los Angeles, CA.

Dear Tologs,

During quarantine, I’ve used my free time to learn more about myself and my family. The mundanity of being stuck at home during much of this past year drove my wife to find new ways to entertain herself and build connections. She decided to perform genealogy research on her family and eventually drew me into that research. I once again was drawn into the extraordinary life of my late Grandpa Toshio (Tom), Yamagata. As I reflected on his life, I was able to draw connections to our modern world and my own experiences. In that light, I want to share a bit of his story with you.

A Global Pandemic

Toshio Yamagata’s life would be very much shaped by the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Toshio was born in 1912 in Fowler, CA. His parents were recent Japanese immigrants who worked hard to build a life for themselves, Toshio and his siblings. Toshio’s father worked as a farmhand, and his mother ran a small boarding house. Then, the pandemic struck. By early 1919, both of his parents would be dead. He was orphaned at the age of six. That year, he and three of his brothers were sent to Japan to live with relatives.

Toshio would spend the next nine years in Japan before the family was able to send him back to the US for high school. By that time, he had to relearn English and move away from his friends and family in Japan to pursue the life his parents envisioned for him. Despite this, he successfully moved back to Fowler, CA and eventually became the valedictorian of his high school graduation class.

Endemic Racism, Economic Turmoil

After high school, Toshio worked for a year to pay off debts he incurred by moving back to the U.S. He was eventually able to attend UC Berkeley, which was already considered a prestigious research university. He earned a B.S. in commerce in 1939. After graduation, however, he found that the job market was not welcoming to him. The nation was still recovering from the Great Depression, which certainly didn’t help with his job prospects. However, Toshio’s status as a Japanese American also proved to be a big barrier to employment. The same xenophobia that would lead to the signing of Executive Order 9066 just a couple of years later meant that many businesses just wouldn’t consider him for employment, even with a degree from a highly regarded university.

In 1940, Toshio moved to Japan in search of employment. His search eventually led him to Harbin, Manchuria, where he was employed as a civilian contractor translating printed media (books and magazines) for the Japanese Imperial Army. During this time, he married my grandmother, Mary Muroya, who also happened to be a Japanese American. Shortly after that, they had a daughter, Miyoko.

In 1945, the Soviets invaded Manchuria. Toshio was taken as a prisoner of war and was sent to a hard labor camp in Siberia to mine coal. Mary and Miyoko, along with the other prisoners’ families, were sent to live in a nearby encampment, withstanding hard, freezing conditions and the brutal oversight of the Red Army for months until they could be relocated to Japan. Eventually, the Red Cross assisted in moving the families to Japan. It was a very hard trip where both Mary and Miyoko suffered from sickness and malnutrition. The Red Cross said they could not guarantee the lives of children under five years old. At the end of this trip, Miyoko succumbed to malnutrition and died. Mary would recall the details of this trip in a letter shared with my mother in 1997. Mary noted that these were very difficult times to reflect on but wanted my mom and my aunt to know about the sister they never knew.

Adapting and Moving Forward

After four years in the Soviet camp, Toshio was repatriated to Japan and reunited with Mary. The two of them would have to restart their life together. He gained employment as an office clerk, and the two had two daughters.

Over the next nine years, it became clear, however, that Toshio would not be able to retire before Japan’s mandatory retirement age. He and Mary came back to the U.S. in the late ’50s with my mom and aunt. To help their daughters assimilate into American society, Toshio and Mary forbade their daughters from speaking Japanese at home to remove any trace of a Japanese accent.

Toshio raised his family in the San Fernando Valley and helped to start a successful landscape gardening business, allowing him to buy a house and put his two daughters through college, an accomplishment of which he was very proud. Although he lost his United States citizenship because of his affiliation with the Japanese Imperial Army, he was never resentful. He lived in the U.S. as the spouse of a U.S. citizen and eventually regained his citizenship through naturalization.

Many aspects of my Grandpa’s life seem wholly extraordinary, but other parts are all too relatable. The world is yet again in a global pandemic; as a society, we are still combating racism and prejudice; and, on a much more personal note, my wife and I just bought our first house in the San Fernando Valley, where we hope for a better future for our family.

I hope you enjoyed the read. If you are wondering about my wife’s genealogy research, she found out that she is likely descended from the Pilgrim who fell off the Mayflower, which I think speaks volumes about my in-laws.

Sincerely,

Dr. Sanderson

Roy Sanderson • Mar 18, 2021 at 7:25 pm

Thanks for writing., my son. Peace and Love to all. Let’s work for humanity everywhere. ✌️❤️