How social media affects political polarization

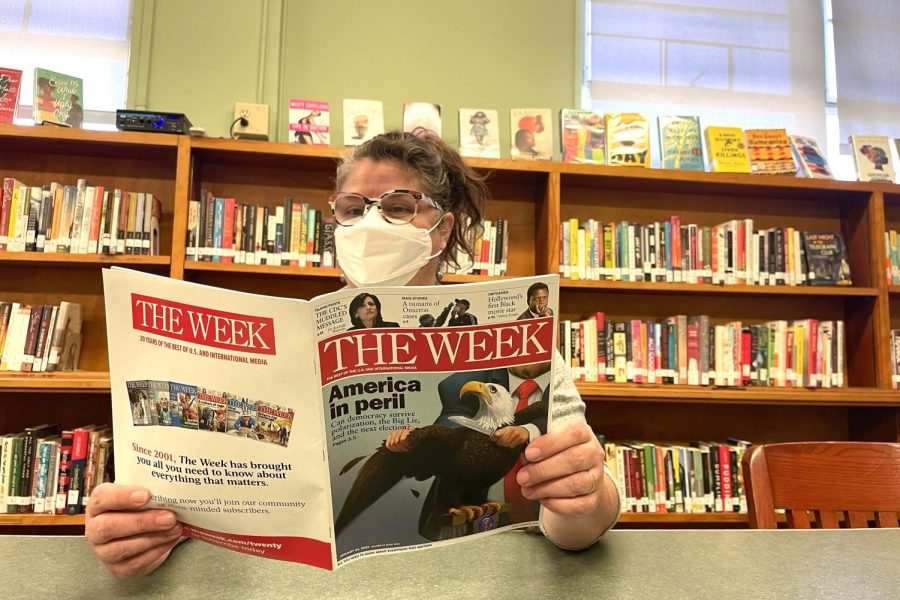

Director of Library Services & Research Program Mrs. Nora Murphy reads a copy of The Week to learn about current events.

It’s a bright and early morning in the 1990s and a teenage Mrs. Nora Murphy, now Flintridge Sacred Heart’s Director of Library Services & Research Program, walks into her living room. She looks out her window and watches her dad walk back into the house, holding the bundle of newspapers he had just bought from the newsstand down the street.

This was a morning ritual he never missed: buying the paper, bringing it home and sitting with his wife as they both read what the world had to offer that day. With the help of these daily newspapers, the televised nightly news programs and a plentitude of current events magazines lying around her house, Mrs. Murphy first became introduced to the world of news.

Today, many teenagers get their news in a different way. According to a Veritas Shield poll, 64% of Tologs get their news primarily from social media.

Social media gives teenagers a multitude of choices when looking to find the news. On platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, people can follow traditional publications, like the New York Times or CNN, and see posts summarizing recently published articles. Users can also follow their friends and the people they know, leading them to see whatever content the people they follow repost or create themselves. It’s also easy to come across clickbait content that doesn’t adhere to journalistic standards.

“I see my friends reposting their opinions, and that’s kind of how I get my news,” Rachel Pangilinan ‘25 said.

However popular social media may be, this shift to using it as a news source can end up perpetuating political polarization. According to a recent study from Trends of Cognitive Sciences, while social media isn’t the root cause of political polarization, it does amplify it.

Social media platforms have uniquely designed algorithms that track scrolling habits, allowing them to cater the content to users’ tastes. For example, if someone likes or shares a post about climate change, the app they’re on is likely to recommend more content related to climate change and similar topics. These algorithms can contribute to confirmation bias, which is the tendency to watch and read information that validates preexisting opinions. This prevents consumers from interacting with news sources that offer different perspectives.

“I think that getting news from social media increases political polarization because I find a lot of the time that social media advertises things towards you based on what they know you like, so I feel like you’ll be getting news that pertains more towards your opinions and beliefs,” Jazmin Jones ’23 said.

News from social media sources also tends to provide a more condensed version of the information that’s found in newspaper articles. For example, on Twitter someone might retweet a headline from The Washington Post, and those seeing that tweet might only choose to read that headline and not the entire article. Seeing only the headline or main idea of a news story can cause people to jump to conclusions, limiting their understanding of the topic.

“Reposting headlines or just the main idea [of a story] ignores the nuance of articles, and additionally, headlines don’t include all perspectives. This could contribute to polarization because people will then only see certain perspectives that often take a very strong stance, due to the nature of headlines,” Aideen Alpuerto ‘23 said.

Social media outlets are not designed to inform their users about current events; they have the potential to do so, but their main goal is to share entertaining content that keeps users glued to their phones. Their goal is to generate clicks and to keep users scrolling, not to educate users on what’s going on in the world.

“If [social media’s] job is not to inform you but just to keep you entertained, and the way it keeps you entertained is by giving you content from something you’ve previously interacted with, you’ll be getting one certain view on the news,” Jones said. “If you went to a news station, whose primary focus is to inform you on what’s going on, that would be better, but to a certain extent, [social media news] can get the gist of what’s going on to you quickly.”

Now, years after her first exposure to the news industry, Mrs. Murphy has some advice to give any high schoolers who get their news on social media.

“You always want to know who’s producing the information you’re consuming, and that’s true everywhere. If you don’t recognize the name of a publication, instead of going to their website to learn about what they are, look them up on Wikipedia for a neutral, third-party perspective. When you know who you can rely on for that kind of information, you never have to think about it again,” Mrs. Murphy said. “There’s a little bit of work that has to be done, but then you establish what I call ‘source literacy,’ which is when you know which sources you trust. Social media does also always have the ability to promote content from newspapers. Yes, look for a variety of sources, but you can also look for them within that social media platform. There are very few news sources out there that don’t make that easy to do on social media now, so there’s really no reason to miss that content.”

Once one figures out how to navigate social media news content, it can end up becoming a beneficial form of media.

“While, yes, it can contribute to polarization when people get stuck in their confirmation bubbles, on the other hand it can be an amazing way to engage with people that you don’t have access to on a personal level. I think it can also increase communication and hearing different perspectives if people really seek that, so it’s really a matter of how you choose to use it,” Mrs. Murphy said.

Graciela Tiu is a senior and an associate editor for the Veritas Shield. She began working for the paper in her junior year, and she plans to continue...