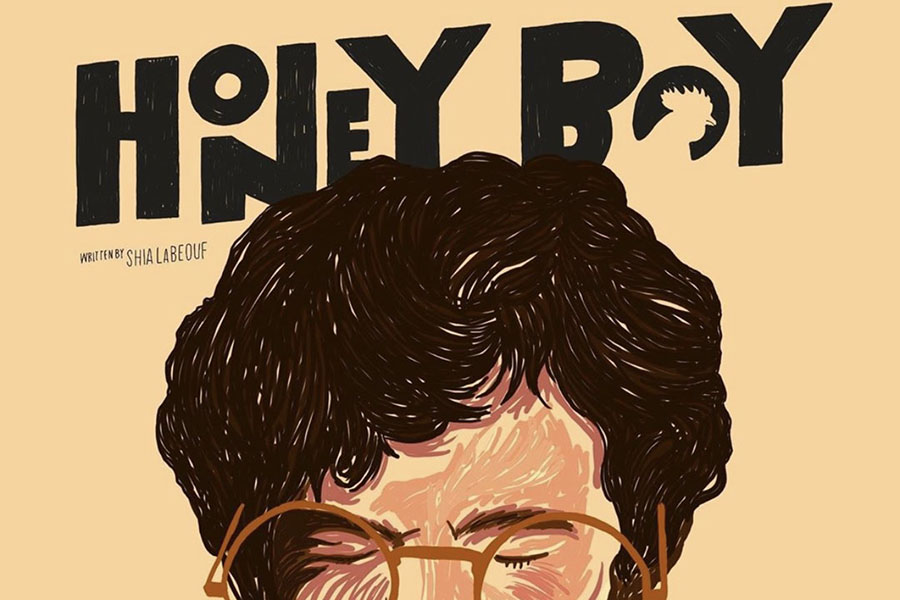

‘Honey Boy’ ain’t so sweet: Shia LaBeouf’s flawed return to Hollywood

“Honeyboy” opened in theaters in November and is now available on Amazon for streaming.

“They’ve got cameras everywhere, you dummy! I’ve got more millionaire lawyers than you know what to do with!” yells a man from the backseat of a police car. An officer outside of the car calmly flips through a pile of papers. The man continues to scream.

Many know him as Stanley from “Holes” or as Louis from the Disney sitcom “Even Stevens” or perhaps as Sam from the “Transformers” franchise, but most cannot forget the image of Shia LaBeouf’s drunken tirade as he was arrested in 2017. After his arrest, LaBeouf’s signature flamboyant persona was quieted, and he was pictured in public donning Uggs a few too many times, leaving people to wonder if he would ever return from his fall from grace.

Well, LaBeouf is back, but not without an explanation. The former blockbuster star has endeavored to repair his image in his latest movie, “Honey Boy,” where he depicts his own childhood trauma, identifying his father’s abuse as the root cause of his alcoholism-induced downward spiral.

In this lightly fictionalized autobiographical movie, LaBeouf plays his real-life father, James (real name Jeffrey LaBeouf) alongside Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges, who play LaBeouf, or Otis, during the child actor and recovering alcoholic phases of his life, respectively. The movie travels back and forth in time as Otis in rehab wrestles with the effects of his father’s abuse on child-actor Otis. In court-mandated therapy, Otis comes face-to-face with the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father, and Otis, in LaBeouf’s very meta way, writes a script to come to terms with the man who raised him.

LaBeouf’s performance as his father is real, unrestrained and, at times, uncomfortable. He paints a picture of a man who is abusive and vulgar but who is also trying to construct a picture of fatherhood from the pieces of his own broken childhood. LaBeouf shows that James is wounded, but, at the same time, he does not excuse his father’s abuse. His depiction of James is transparent, undoctored, holistic. The man who slaps Otis and calls him names is the same man who sometimes holds his hand and plays cards with him. In his portrayal of James, LaBeouf shows the contradictory reality of abusive relationships. It is clear that even though LaBeouf sees all of his father’s shortcomings, he loves him, which is exactly what, at times, makes this movie uncomfortable. No matter how much James belittles or embarrasses Otis, Otis still loves him and wants to be loved by him, even if it means being let down time and again.

LaBeouf is a natural talent. Consistently, his performances have been impressive since his breakthrough role in the 2007 film, “Disturbia.” It is no wonder then that his portrayal of his own father, a man he spent years analyzing, is great. But his performance is marked with the faint scent of his self-indulgent public persona that “Honey Boy” was supposed to shed. The camera often focuses on LaBeouf for prolonged periods while he spouts abuse, racist jokes and self-pitying tirades — God forbid we forget for a moment this movie is all about Shia! — and these moments become repetitive and tiresome as the movie slows to a stop. His performance parallels the offscreen theatrics that the public initially endured but then grew weary of.

That said, the performances in “Honey Boy” are often wonderful. Twelve-year-old Jupe finds a depth of emotion that many child actors are unable to tap. Hedges is good as well, though his performance feels similar to many of his past roles. From “Manchester by the Sea” to “Mid 90s,” he seems to play a variation of the same brooding, frustrated character. Even so, this mold fits the character of Otis, especially the anger he feels as he is forced to confront his past in rehab.

Unfortunately, the movie’s writing and direction undermine the actors’ strong performances. The script, which was written by LaBeouf, is littered with repetitive scenes that drag the movie to its facile conclusion. Although the movie’s runtime is only an hour and 35 minutes, there are moments when it feels as long as “The Irishman.” During these moments I couldn’t help but think, “Just do it!” That is, just end the movie already.

“Honey Boy” is directed by Alma Har’el, an Israeli filmmaker who first gained acclaim for her 2012 documentary “Bombay Beach.” Har’el’s work on “Honey Boy” has received considerable praise, which may stem from the excitement people (myself included) feel when a female director successfully emerges in Hollywood. But, regardless of gender, the direction lacks nuance and, as a result, makes for some cringeworthy moments. For example, there is one scene where young Otis and his older teenaged love interest (the relationship is weird) are sitting by the pool in the motel where they live. Otis approaches the girl and sees that she is watching a water snake glide on the pool’s surface. Otis asks her what the creature is (it is clearly a snake, but that’s beside the point). Instead of looking mystical, the blue light emanating from the motel signs lights their faces in an odd, tacky way. The girl, played by FKA Twigs, says, “You can walk on water until someone tells you you don’t know how to,” and asks Otis if he understands. Because of how the scene is executed, it feels tryhard instead of profound or revelatory, which is the movie’s main problem. Sure, there are some compelling visuals and color schemes. Sure, much of the soundtrack is catchy and harkens back to Ha’rel’s experience directing music videos. But these things are just Band-Aids stuck onto deeper wounds. The movie walks the line between self-exploration and self-justification, in the end leaving viewers wanting something more.

Ella Kitt is the editor-in-chief. She joined the Veritas Shield writing staff as a sophomore in 2018 and served as the managing editor her junior year....